An international, interdisciplinary research team recently read a letter from July 31, 1697—without opening or damaging it. The research group, called Unlocking History, has made major, exciting leaps forward in the areas of letterlocking and virtual unfolding. This advance in technology may have important implications in the study of historic documents and for the field of cultural heritage.

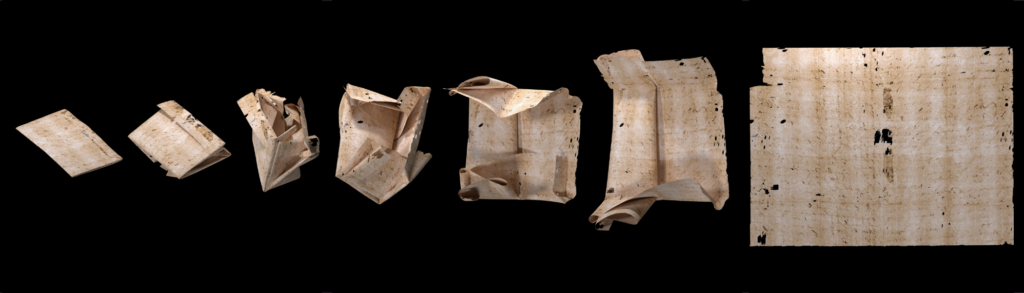

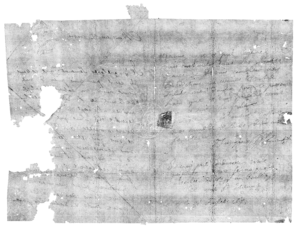

Before the envelope became widely used in the 1830s, letterlocking was a system of securing a letter’s contents through intricate methods of folding. By applying a computational flattening algorithm that can detect and unravel data to a trunk full of undelivered mail, the researchers performed a virtual unfolding of an unopened letter from 1697, allowing them to legibly read text without damaging the document or opening the letter.

As the research team notes: “This algorithm takes us right into the heart of a locked letter. Sometimes the past resists scrutiny. We could simply have cut these letters open, but instead we took the time to study them for their hidden, secret, and inaccessible qualities. We’ve learned that letters can be a lot more revealing when they are left unopened. Using virtual unfolding to read an intimate story that has never seen the light of day – and never even reached its recipient – is truly extraordinary.”

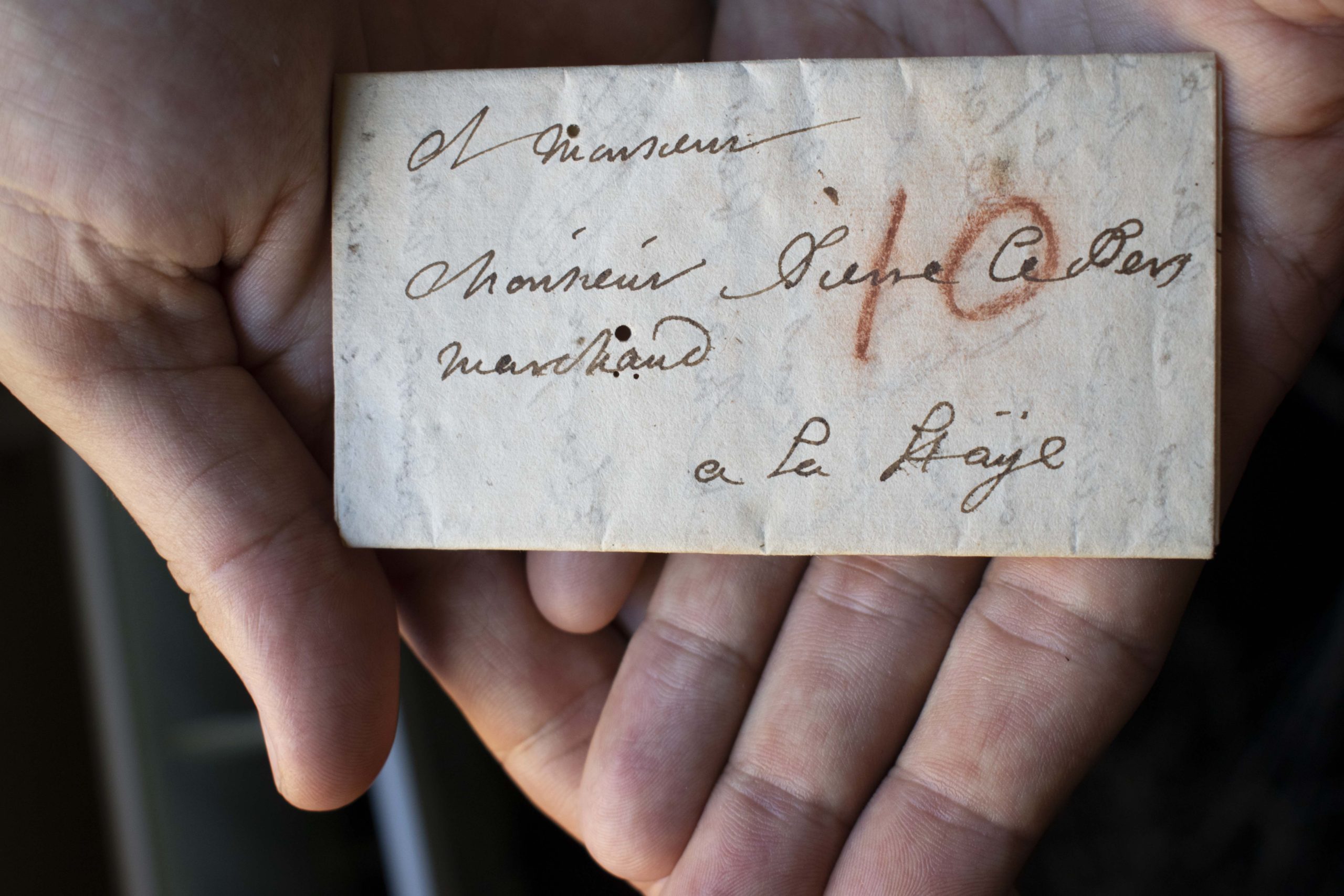

The unlocked letter was written by Jacques Sennacques to his cousin Pierre Le Pers, a French merchant, asking for a certified copy of a death notice of a family member. This letter provides insight into the lives of ordinary people during a period of European history wherein letters connected families and friends over vast distances.

Various techniques of letterlocking have been employed over hundreds of years. Some techniques even had contrivances to let someone know if the wrong person attempted to read the contents. The research team created what the project’s Twitter thread calls “the ‘periodic table’ of letterlocking,” which helps researchers to navigate the various folding methods used to lock a letter. The table also provides a way to score the security of different letterlocking approaches based on how easily the letters could be intercepted and read by unintended recipients.

Prior to the availability of virtual unfolding technology, researchers had to physically open the letters in order to understand letterlocking and to read the message inside, which tampers with the pristine interior condition of the letter. Researchers can now avoid this traditional pitfall by using computational analysis and virtual unfolding to read letters without opening them. This project is significant for the fields of preservation and conservation because it will allow researchers to glean knowledge while keeping letters intact.

The small team of eleven researchers at Unlocking History includes three women without PhDs. One of the authors of the report, Holly Jackson, started with the project team while she was in high school. She now attends the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As the project’s Twitter thread points out, “a PhD is not the only way into scientific research.”

The 1697 letter is from the Brienne Collection, which includes over 570 sealed letters from the 17th century and is held by Sound and Vision The Hague, The Netherlands.

The full results of the project can be found in a March 2nd, 2021 Nature Communications article entitled, “Unlocking history through automated virtual unfolding of sealed documents imaged by X-ray microtomography.” To learn more, please check out the project’s Twitter thread, YouTube channel, and two project websites: http://letterlocking.org/ and http://brienne.org/. There is also an online Q&A with the team which can be found on their Facebook page here.

Christine Grubbs is the Special Projects Manager and Lucy Matthews is the Projects & Research Manager at Cultural Heritage Partners.