November 2021 will mark four years since French President Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the University of Ouagadougou, in Burkina Faso, when he declared one of his priorities would be to establish conditions within five years “for temporary or permanent returns of African heritage to Africa.”[1] One year after that speech, in November 2018, Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy published their report, commissioned by Macron, addressing the restitution of cultural heritage held in French national collections.[2]

Although the Sarr-Savoy Report was limited to sub-Saharan Africa, its impacts were much broader, ushering in a new cognizance about the scope of the problem of art looted under colonial rule worldwide and pushing countries and museums to consider restitution. Nearly three years after the French report, the results are mixed, with some countries making faster progress than others.

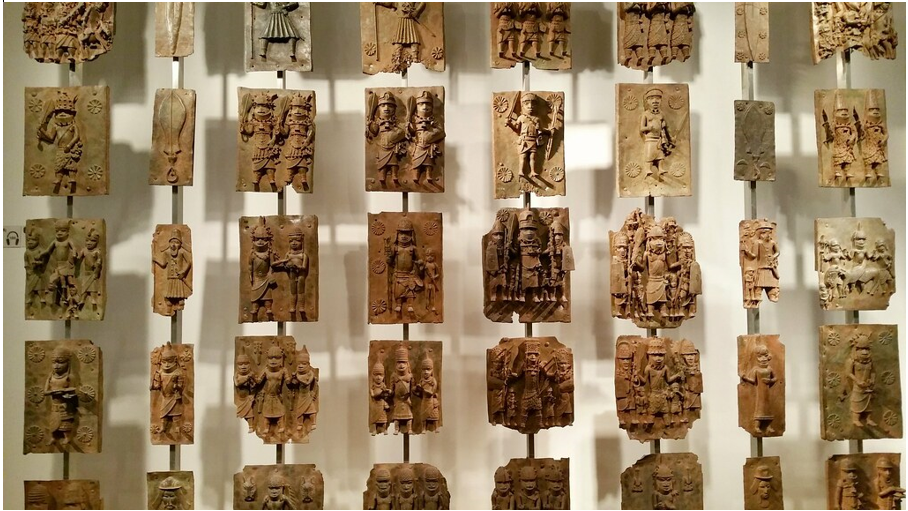

The Benin bronzes––thousands of sculptures and plaques looted by the British in a violent 1897 attack––have become the symbol of the movement to return art looted under colonial rule, although some have complex ownership histories since their initial looting.[3] The Edo Museum of West African Art, now being built in Benin City, Nigeria, will display restituted Benin bronzes.

Germany was early to respond after publication of the French report, with its 16 states adopting guidelines for colonial collections in 2019. More recently, Germany committed to returning its Benin bronzes beginning in 2022.

France has been slower to implement the broad recommendations Sarr and Savoy proposed, such as adding exceptions to the general principle in French law that state collections are “inalienable” absent specific legislation. France has passed a law authorizing the return of 27 objects to Benin and Senegal––but without broader measures, each new restitution will require separate legislation.

Other countries have adopted national policies (albeit after initial delay in some cases). The Dutch government announced in January 2021 that it would unconditionally return objects looted from former Dutch colonies as well as consider claims for objects looted from non-Dutch colonies and for objects of particular significance to a claimant, even absent express evidence of theft.

In June 2021, Belgium agreed to develop a bilateral accord with the Democratic Republic of Congo to address works looted during colonial rule. This agreement came only weeks after a report by Belgian scholars and experts calling for action and setting out recommendations to address the country’s colonial collections.[4]

Movement in the U.K. has been more staggered, with broadly-applicable guidelines yet to be adopted in England. Although the government-funded Arts Council of England appointed the Institute of Art and Law to develop guidance for museums on restitution, the pandemic has delayed their publication.[5] Scotland has made more progress, with the National Museums Scotland recently adopting procedures for considering restitution requests and the University of Aberdeen announcing that it would repatriate a Benin bronze looted during the 1897 raid to Nigeria. Indicating a possible shift in public opinion, the Aberdeen decision was supported by The Times (of London) in an editorial.[6]

In the United States, where most museums are not government-owned and therefore lack central control, the conversation has been advancing even more slowly. The Association of Art Museum Directors and American Alliance of Museums often take up this type of issue and develop guidance for their members, but have not yet acted. The AAMD announced in late 2019 the formation of a task force to address the issue of art looted during colonial rule, but there have been no evident developments. (A similar AAMD task force in the 1990s developed guidelines on Nazi-looted art which laid the foundation for the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art.)

A common thread in the guidelines and procedures released so far is that objects looted by military forces or with specific evidence of theft should be candidates for return. Many such objects have insufficient documentation and most of the guidelines therefore call for provenance research (though only a few countries have provided funding) and sharing the results of that research with possible claimants. A limiting factor in certain guidelines is scope––the French Sarr-Savoy Report, for example, is limited to objects in national institutions coming from sub-Saharan Africa, despite the fact that France had colonies elsewhere and colonial objects can be found in other French collections. As repatriation procedures begin to materialize and restitutions follow, it remains to be seen whether there will be an international effort to harmonize the guidelines or speed up the pace of decision-making.

Olga Symeonoglou is an attorney in the DC office of Cultural Heritage Partners.

——————-

[1] https://www.elysee.fr/en/emmanuel-macron/2017/11/28/emmanuel-macrons-speech-at-the-university-of-ouagadougou

[2] http://restitutionreport2018.com/sarr_savoy_en.pdf

[3] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/09/arts/design/met-museum-benin-bronzes-nigeria.html

[4] https://restitutionbelgium.be/en/report

[5] https://ial.uk.com/arts-council-england-appoints-ial-to-develop-new-guidance-on-restitution-and-repatriation/

[6] https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/the-times-view-on-returning-benin-bronzes-home-territory-gjcrb6n5j

Photo credit: The Benin bronzes have been the subject of some of the loudest calls for return, given their cultural and art historical significance as well as the violence of their removal from the Kingdom of Benin (now in Nigeria) in 1897 by British forces. Benin Bronzes by archieflickers is licensed under CC BY 2.0